Russia’s intervention in Syria in 2015, and then subsequently in Libya, marked its return as a major actor in the Mediterranean. Much has been made of Russia’s use of all elements of statecraft, including diplomatic, ideological, military, and economic instruments, to advance its interests in this region, a vital shipping and transit corridor. A closer look at Russia’s economic tool kit in this region, however, suggests concerns about Russian economic capabilities are likely overstated.

Russia’s most important economic tools in the Mediterranean are its energy resources, arms exports, and ability to launder money through corrupt networks. These tools have complemented Russia’s diplomatic and military activities, particularly in areas where economic systems and rule of law have been weaker. Where Russia has been successful, it has increased a country’s dependence on Russian money, oil and gas, and/or arms, giving it a say in a country’s policymaking, particularly on matters of importance to Russia, and a way to undermine U.S. and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization’s (NATO) influence in the region.

In particular, Russia’s unique economic tools have helped it manage its otherwise difficult relationship with Turkey, which depends on Russian oil and gas and is a new customer for Russian nuclear power and weapons systems. Turkey is a unique example in the Mediterranean where Russia already had a substantial trade and investment relationship beyond hydrocarbons, and then used these newer, more subversive tools to build its influence. These same tools have allowed Russia to gain more influence in Egypt, Algeria, and to some degree Cyprus over the last decade.

These tools have proved of limited utility elsewhere, however, as they have not been backed by the traditional instruments of economic statecraft: trade in non-energy goods and services, foreign direct investment, and development assistance. Russia has trailed the United States and Europe, and in some cases China, in deploying these fundamental economic elements of foreign policy in the Mediterranean region. Based on economic data available, Russia’s bilateral trade with individual Mediterranean countries is low, its investment levels in most Mediterranean countries are insubstantial, and it is not giving large quantities of development assistance to the poorer countries along the Mediterranean’s eastern and southern rims. The lack of these traditional economic ties is surprising, given Russia’s military and diplomatic efforts to increase its influence in the region. Without them, Russia’s economic diplomacy in the region is highly based on symbolism and the relationships lack sustainability over the long term, which undercuts its geopolitical ambitions in the Mediterranean.

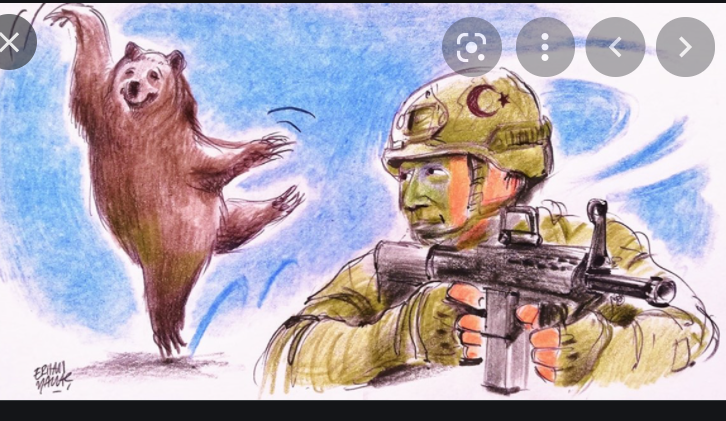

Russia and Turkey

Not all Mediterranean countries import Russian gas, as distance and/or local supplies make Russian piped gas cost-prohibitive or unnecessary. These factors force Russia to focus on Southern Europe, but it must do so with Turkey serving as a central node and partner, especially since its previous efforts to build pipeline infrastructure around the country have come to naught. The Kremlin has been remarkably successful in maintaining increasingly close energy cooperation with Ankara despite being on opposite sides of three different regional conflicts in recent years, largely by compartmentalizing disagreements and playing to President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s disenchantment with the West and ambitions to make Turkey a regional gas distribution hegemon. Russian-Turkish energy cooperation has led to the completion of several large-scale pipeline projects.

Beginning with the Blue Stream pipeline, which was completed in 2003, new pipeline projects have increased Turkey’s consumption of Russian gas while allowing Russia to bypass Ukraine to send gas to Southern European destinations—a clear win for both countries. As of January 2020, when the Turkstream pipeline across the Black Sea began operations, Turkey stopped receiving Russian gas through the Trans-Balkan Pipeline from Ukraine, which it had done since the mid-1980s. The second phase of Turkstream envisions extending the pipeline through Bulgaria all the way to Hungary, weakening Ukraine’s position as a transit state and transforming Turkey into a more important node for gas deliveries to Europe, again a win for both Moscow and Ankara.

Still, the example of Turkey illustrates the limits of natural gas as a lever of influence for Russia. The shale gas revolution has drastically brought down the cost of natural gas, reducing the revenues Russia can gain from gas sales, while the EU’s Third Energy Package has limited its monopoly power over gas distribution.

According to data from the Bank of Russia, the country’s revenues from global gas exports peaked in 2013 at $71.5 billion, and they have not returned to near that level since, with the global recession spurred by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 bringing the total down to $32 billion, a level not seen since 2005 (see Figure 1). Moreover, the spread of liquefied natural gas (LNG) technology allows countries to import gas from anywhere, free from a dependency on pipelines that are costly to build and maintain. By expanding its use of LNG (as the third-largest importer in the world in 2020), Turkey no longer has to rely solely on piped gas from Russia, Azerbaijan, and Iran, but is diversifying its supply from at least seven new partners, including increasing volumes from the United States. In 2020, Russia remained Turkey’s largest gas supplier at 16.3 billion cubic meters, but imports of gas from the United States grew by 144 percent to 3 billion cubic meters. Turkey also has long-term contracts for LNG with Algeria and Nigeria. Moreover, by becoming a central node in Russia’s gas distribution system, Turkey gains the same leverage Ukraine used in the past—the ability to negotiate down the price it pays for its own imports in order to allow Russian gas to flow through its territory and on to the rest of Europe. Taken together, these steps have reduced Russia’s ability to use gas as political leverage with Turkey, even if they have not eliminated it. Moreover, cooperation on gas projects is in the interests of both countries as they look to expand their influence in Southeastern Europe.

NUCLEAR POWER PLANTS

Another key part of Russia’s economic influence tool kit globally is the conclusion of deals to build nuclear power plants abroad. The Russian national security establishment views civilian nuclear power exports as an important tool for projecting influence as well as creating revenue streams for sustaining intellectual and technical capabilities and vital programs in Russia. Nuclear power plants are expensive, however, and not without risk. They can be of dubious value to the host government, or saddle the state nuclear power monopoly Rosatom with debts it cannot collect. Therefore, Russia has more often than not overpromised and underdelivered when signing agreements to build nuclear plants. Most are never fully implemented.

Rosatom has signed agreements, however, with Turkey and Egypt for large nuclear plant projects. Turkey signed its agreement in 2010 under which Rosatom will build, own, and operate the country’s first nuclear power plant at Akkuyu, which will have a total capacity of 4,800 megawatts (MW).This model means Rosatom will have a long-term presence at Akkuyu, with near-complete operational control over the plant. The company plans to open the first unit of the four-unit plant in 2023, in time for the hundredth anniversary of the Turkish republic.

Like other Rosatom projects around the globe, the Turkish and Egyptian nuclear power plants appear to be geopolitical projects of somewhat dubious economic merit, but it seems unlikely Russia would be able to replicate this model elsewhere in the Mediterranean.

ARMS SALES

Continuing its decades-long legacy, Russia was the world’s second-largest exporter of arms, after the United States, between 2016 and 2020. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), it accounted for 20 percent of all arms exported during this period. Russia’s arms sales provide it direct engagement with foreign countries’ leaders, relationship-building tools with their militaries, and profits for its arms-producing enterprises. This is a major tool Russia uses for influence in the Mediterranean, but with most of the northern littoral states being NATO members, its arms-sales relationships focus on the eastern and southern ones.

WATCH: Turkey’s Convoluted Foreign Relations | Real Turkey

Turkey is also a success story for Russia’s arms sales strategy. As a long-standing NATO ally, Turkey did not purchase Russian arms between 1950 and 2017, other than some second-hand armored personnel carriers and helicopters in the early 1990s to be used by the police. Instead, Turkey imported arms only from other NATO allies, and developed its own arms industry. According to SIPRI, from 2016 to 2020 Turkey dropped from being the sixth-largest arms importer to the twentieth, due to the development of its own defense industry.

Yet in 2017, it agreed to purchase the S-400 missile defense system from Russia over the strong objections of the United States and other NATO allies. At the same time, the U.S.-Turkish relationship had deteriorated over differences on cooperation with Syrian Kurdish forces, the 2016 attempted coup in Turkey, and the subsequent U.S. refusal to extradite cleric Fetullah Gülen, as well as Washington’s reluctance to sell Patriot air defense systems on Turkish terms. Turkey felt the United States and NATO had done little to help it reduce its vulnerability to attack from the conflict in Syria. Moscow capitalized on this frustration with the West and vulnerability to Russia’s role in Syria to offer the S-400 system, which Erdoğan quickly accepted.

WATCH: Turkey and US: Final Countdown | Real Turkey

This sale was a clever move to drive a wedge between Turkey and its NATO allies, as the United States was forced to respond by removing Turkey from the F-35 fighter jet program for fear of release of sensitive technology to Russia through the S-400 system. Discussions reportedly continue between the Turkish government and the Biden administration on a path forward on the issue of the S-400 system, which Turkey has tested but which is not yet in full use.

In this case, the sale of a weapons system met Russia’s economic, military, and geostrategic goals in one tidy package—a model Russia likely will look to replicate elsewhere, if the right factors are present.

This is an excerpt from Carnegie International report, link to full article is here

Follow our English language YouTube videos @ REAL TURKEY: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCKpFJB4GFiNkhmpVZQ_d9Rg

And content at Twitter: @AtillaEng

Facebook: Real Turkey Channel: https://www.facebook.com/realturkeychannel/