Şahap Kavcıoğlu, the third central bank governor in less than three years, presented Turkey’s second quarterly inflation report of 2021 on Thursday.

As expected, the bank raised its year-end inflation estimate to 12.2 percent from the 9.4 percent target set by previous governor Naci Ağbal in January. The bank cited higher import prices due to a significant depreciation of the lira as the main reason for the increase. Domestic demand, which Kavcıoglu said remained strong despite monetary tightening performed by Ağbal, contributed 0.4 percentage points to the hike, as did accelerating global good price inflation.

Scrutinising the details of the latest report, the central bank has completely overlooked a critical factor in stronger inflation dynamics, acting as if it never happened.

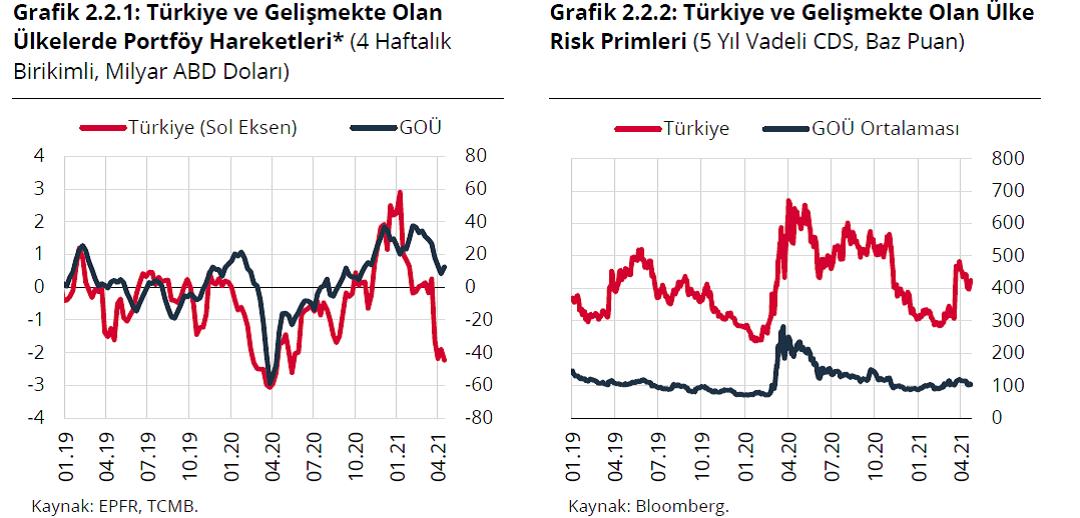

As the charts from the central bank’s report show below, a sharp rise in U.S. 10-year bond yields was the major contributor to an outflow of capital from developing countries (GOÜ). This trend began at the end of January (left graphic-black line), but something starkly different then occurred in Turkey. From mid-March on, capital began to flee the country as if it were being chased with a gun (left graphic-red line).

Capital outflows from developing countries were due to the rise in U.S. bond yields, so there was no general deterioration in the countries’ risk premiums (right chart-black line). In Turkey, the risk premium increased in the middle of last year as the central bank’s foreign currency reserves melted away. The situation then normalised to some extent after President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan employed Ağbal in early November and he tightened monetary policy significantly. But then, as we can see in the right-hand chart, the risk premium for Turkey shot up to around 500 points in mid-March, when capital flight resumed in earnest.

However, we know the answer very well.

Erdoğan, who sees the central bank as his personal territory and intervenes in monetary policy for political purposes, sacked Ağbal four months after appointing him, and replaced him with Kavcıoğlu.

We know that the quarterly inflation report is prepared by a technical team at the central bank, and that the cause and effect relationships are in line with economic logic. However, between the lines there are signs of intense outside intervention in the report. Inflationary pressures are explained by higher commodity prices, supply shortages, the effects of U.S. bond interest rates on emerging market currencies, the strength of domestic demand, growth in domestic bank lending, the pass-through from lira weakness to inflation and high inflation expectations.

However, the report neglects to mention several essential points, namely poor central bank credibility, net foreign exchange reserves running at a negative $48 billion, the change of central bank leadership on March 19 and the 15 percent depreciation in the lira thereafter.

Those who watched Kavcıoğlu’s online presentation of the report were probably not too focused on the higher inflation forecast, the lack of reality therein, or his constant pledges to keep monetary policy tight. There is a general expectation that Turkey will not find it easy to keep inflation at below 15 percent this year after the recent negative events.

However, some viewers of the presentation could not help focusing on the apparent difficulty Kavcıoğlu experienced in reading from its text, perhaps because he is deeply unaware of the terms, phrases and workings of central banking, or how he answered the questions of economists and journalists by reading from a pre-prepared document placed in front of him instead of responding by using his natural intellect and knowledge.

The governor’s constant depiction of tight monetary policy as a policy interest rate “above current and expected inflation” also probably did not go unnoticed by onlookers.

When asked about omitting a previous pledge to tighten rates if needed from a document accompanying the bank’s April decision to keep rates steady, it seemed incredulous for Kavcıoğlu to urge economists “not to focus on the concepts that have been eliminated from the text but to focus on his promise of tight monetary policy”.

The central bank is displaying a neurotic disconnection from reality and the truth by pretending that a 15 percent depreciation in the lira did not occur as a result of a change in governor.

Kavcıoğlu’s constant insistence that tight monetary policy equals keeping interest rates at an undefined margin above inflation indicates that rate cuts will start sooner rather than later, probably by the mid-summer.

If some people are still not convinced that the economy is in a dead end after unqualified people wasted away $128 billion of the central bank’s foreign exchange reserves, they soon will be by Kavcıoğlu’s near-term monetary policy choices, as rate cuts are due to start in July or August.

The effects of the upcoming, mistimed rate decreases on the lira, inflation, foreign debt, the risk premium, capital flows and the overall economy will be remembered for years to come as the moment that determined the fate of the current Turkish government.

Ahval