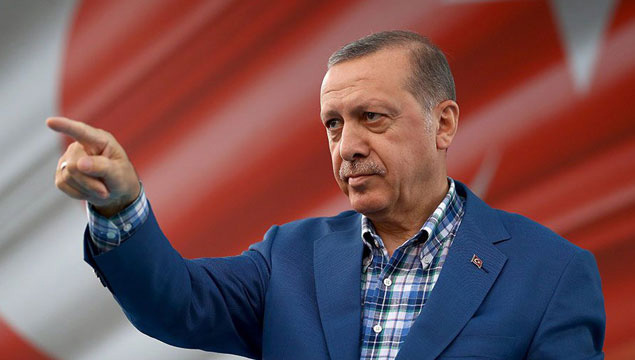

The man who stands to shape Turkey’s historic election next month — in which President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is seeking to consolidate his 20 year grip on power — is running his campaign from a prison cell, and he reckons he has an edge.

Selahattin Demirtaş, a former presidential candidate and party leader, is spending his seventh year behind bars on terrorism charges in a high-security prison near the Greek border. Even so, he still wields huge influence in the knife-edge May 14 presidential and parliamentary election, largely because of the votes of millions of Kurds, who represent around a fifth of the NATO member’s population of 85 million.

Those Kurdish votes are now likely to prove decisive, and Demirtaş estimates his party, the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), represents about two-thirds of them. “In this critical election where even half a percent is crucial, Kurdish voters will be very influential in determining the outcome,” he told POLITICO in an interview conducted via his lawyers, even as he complained that “it is very difficult to follow and participate in politics from a high-security prison.”

Turkey’s election is turning into one of the most closely watched political showdowns of the year, with massive strategic implications for Europe and the Middle East. Many see the vote as a crux moment to wrest democracy back from Erdoğan’s increasingly centralized rule, but the Islamist populist president himself will be hard to beat, being a veteran campaigner with deep grass-roots support, who can draw on the full resources of the state and a pliant media culture.

In an attempt to break Erdoğan’s grip, six opposition parties have gathered behind Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, as a united challenger for the presidency. Demirtaş’ HDP has not formally joined this alliance, but is boosting Kılıçdaroğlu’s cause by not fielding its own nominee for president.

While Erdoğan is certainly more vulnerable this year than ever before because of runaway inflation and increased frustration over cronyism and mismanagement, the election still appears too close to call, with polls generally showing narrow leads for the challenger.

Enter the kingmaker

Demirtaş first gained international attention as a force in Turkish politics almost a decade ago, when he established his reputation as a kingmaker. A songwriter, award-winning author of five books and a human rights lawyer, he performed strongly in Turkey’s 2014 presidential race, when he went far outside his Kurdish base to scoop up almost 10 percent of the total vote, and in the 2015 legislative polls when as his party’s joint leader he secured 80 parliamentarians, depriving Erdoğan’s AK party of a majority.

To Demirtaş’ supporters, this is precisely why Erdoğan is trying to neutralize him.

Demirtaş himself stresses that Kurdish frustration with the governing party has only grown since his initial political breakthroughs.

“In recent years, due to Erdoğan’s authoritarian pressure policies, Kurds have become targets along with all opposition groups. Twelve elected Kurdish MPs, 102 mayors, and thousands of party officials and sympathizers have been imprisoned. Governors and other state officials were appointed as trustees to their municipalities. Erdoğan has turned to an extreme nationalist policy that openly displays hostility towards Kurds and has lost a significant amount of Kurdish support,” he said.

To many, Demirtaş’ plight has become a case study of the sheer scope of Erdoğan’s power.

It’s been three years since the European Court of Human Rights called for Turkey “to take all necessary measures” to secure Demirtaş’ release, ruling that his imprisonment violated not only his own rights to liberty, security and freedom of expression but his country’s right to free elections. It concluded that the reasons for his arrest had been a cover for an ulterior political purpose.

Erdoğan has brushed that 2020 verdict aside, insisting that “the ECHR cannot decide in place of our courts.” The president condemns the opposition broadly as terrorist-sympathizers for supporting the move by the ECHR to free Demirtaş. The HDP party he condemns as a parliamentary offshoot of terrorists.

The HDP itself, Turkey’s third biggest party, faces possible closure. That is because of a criminal case centered on what prosecutors say are the party’s links with the PKK, an armed Kurdish group deemed a terrorist organization by Turkey, the EU and the U.S.

politico.eu