Head in the Sand: The Gap Between Turkey’s Grand Rhetoric and Its Munich Absence

munich sec con

munich sec con

By Yavuz Baydar

Summary:

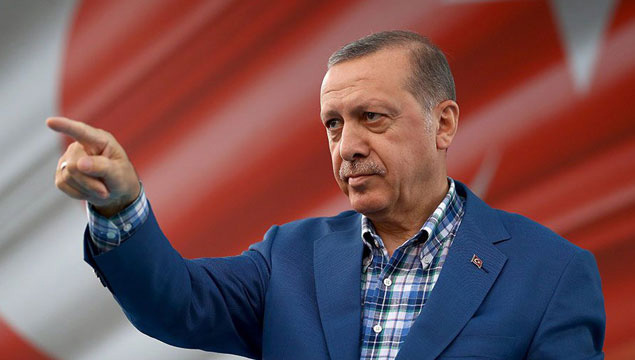

As global leaders gathered at the Munich Security Conference to debate the future of Ukraine, transatlantic relations, and the emerging multipolar order, Turkey — a NATO member with pivotal geography — was notably absent at the highest level. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and the foreign minister did not attend, and Economy Minister Mehmet Şimşek withdrew from a Syria panel. The episode, critics argue, reflects a broader pattern of diplomatic isolation, strategic inconsistency, and democratic backsliding that has steadily reduced Turkey’s influence in shaping the new global order.

A Conspicuous Absence in Munich

The Munich Security Conference has, for six decades, served as one of the world’s premier platforms for debating global security and geopolitical realignment. This year’s agenda was particularly consequential: the future of Ukraine, U.S.–EU relations, Middle Eastern recalibrations, transatlantic cohesion, and the broader architecture of an emerging multipolar world.

Yet Turkey — a NATO member since 1952 and a country straddling Europe, Asia, and the Middle East — was represented neither by its president nor its foreign minister.

The only senior official scheduled to attend was Economy Minister Mehmet Şimşek. Even that presence proved short-lived. Şimşek was due to participate in a panel on Syria’s future, a conflict in which Turkey has played a direct military and political role for more than a decade. Shortly before the session, he withdrew.

The reason cited was the participation of two Syrian Kurdish figures, Mazloum Abdi and Ilham Ahmed. Rather than engaging in discussion over reconstruction, refugee return, and regional security, Ankara opted to step back from the debate entirely.

For critics, the episode symbolizes a deeper diplomatic retreat.

“Precious Solitude” or Strategic Isolation?

Turkey’s leadership has frequently framed its foreign policy stance as one of principled independence — sometimes described as “precious solitude” (değerli yalnızlık).

However, observers argue that this rhetoric masks a growing pattern of self-exclusion from key international platforms.

As major powers gather to shape new frameworks for trade, security, technology, and climate cooperation, Turkey’s voice has been increasingly absent. In diplomatic circles, a cynical remark has circulated: instead of being “at the table,” Turkey risks being “on the menu.”

Grand declarations of becoming a “global power” contrast with an unpredictable foreign policy that has, critics say, eroded trust among allies. At a moment when the international system is undergoing structural transformation, predictability and reliability carry heightened importance.

The First Missed Moment: Post–Cold War Democratization

The fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 marked a turning point across Europe. Countries emerging from the Warsaw Pact embraced democratic reforms, civilian oversight of the military, and integration into European institutions.

Turkey, by contrast, maintained strong military tutelage over civilian politics throughout the 1990s. The February 28, 1997 intervention — often referred to as a “post-modern coup” — removed an elected government through indirect pressure rather than direct military takeover.

While Central and Eastern European states moved toward European Union membership, Turkey remained entangled in internal power struggles and unresolved political questions, including the Kurdish issue.

Critics argue that this period represented a lost opportunity to consolidate democracy at a pivotal historical juncture.

The Second Turning Point: The EU Path Reversed

Turkey’s EU candidacy, confirmed in 1999 and formal accession talks launched in 2005, initially generated reform momentum. Early Justice and Development Party (AKP) governments implemented constitutional changes, expanded civilian control, and adopted measures aimed at meeting EU criteria.

Over time, however, reforms slowed and eventually reversed. Political tensions with key EU leaders, including France and Germany, coincided with growing domestic polarization.

The 2013 Gezi Park protests marked a significant inflection point. The government’s response — characterized by forceful policing and accusations of foreign conspiracies — drew criticism from European institutions and rights groups.

Following the failed 2016 coup attempt, extensive purges, arrests of journalists and academics, and constitutional amendments expanding presidential powers deepened concerns over democratic backsliding.

EU accession negotiations effectively stalled, leaving Turkey outside the core of European political decision-making.

The Present Moment: Limited Leverage in a New Order

Today, as global power dynamics shift in response to the war in Ukraine, technological competition, and climate pressures, Turkey faces questions about its strategic positioning.

Ankara has pursued a policy balancing NATO membership with procurement of Russian S-400 air defense systems, involvement in Syria and Libya, and fluctuating relations with neighboring states.

Supporters argue this reflects strategic autonomy. Critics describe it as tactical maneuvering without long-term coherence.

The Munich withdrawal from discussions involving Syrian Kurdish representatives highlighted Ankara’s continued sensitivity over Kurdish political actors — even when broader regional stability is at stake.

Domestic Pressures and External Perceptions

Turkey’s economic challenges and inflationary pressures have also shaped its international posture. Western capitals have raised concerns about judicial independence and political detentions, while Ankara maintains that its actions are guided by national security considerations.

According to opposition lawmakers and rights monitors, tens of thousands of individuals face politically linked charges — a claim disputed by government officials.

These domestic debates intersect with foreign policy, influencing perceptions of Turkey’s reliability and long-term direction.

A Strategic Crossroads

Turkey entered the post–Cold War era with substantial advantages:

-

A young population

-

Strategic geography

-

NATO membership

-

EU candidacy

-

Historical and cultural ties spanning continents

Three decades later, its role in shaping the international order appears more constrained.

The key question is whether Ankara will recalibrate — strengthening democratic institutions and reasserting itself in multilateral diplomacy — or continue to emphasize autonomy over alignment.

As Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney recently remarked in a different context: “Nostalgia is not a strategy.”

For Turkey, the coming years may determine whether it reclaims a central role in global governance debates — or remains on the margins of decisions shaping the 21st century.

Pls click the link to read Yavuz Baydar blogs. Reprinted with author’s permission

PA Turkey intends to inform Turkey watchers with diverse views and opinions. Articles on our website may not necessarily represent the view of our editorial board or count as endorsement.

Follow our English YouTube channel (REAL TURKEY):

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCKpFJB4GFiNkhmpVZQ_d9Rg

Twitter: @AtillaEng

Facebook: Real Turkey Channel: https://www.facebook.com/realturkeychannel/