Minimum Wage Dreams Collapse: 46 Years for a Home, 16 Years for a Togg

minimum-wage

minimum-wage

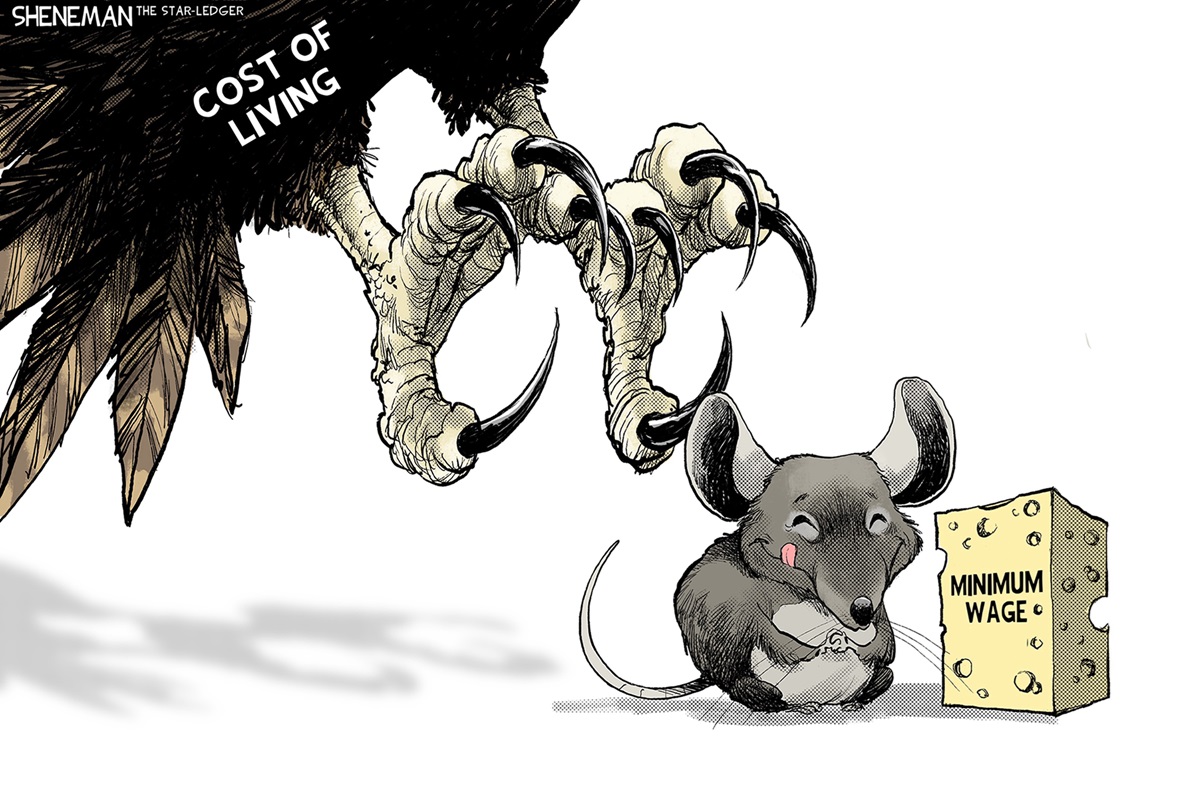

For millions of minimum wage earners in Turkey, the dream of owning a home or a car is increasingly colliding with economic reality. Fresh analyses based on official data reveal that even decades of disciplined saving may not be enough to access basic assets such as housing or transportation. As debates intensify over the 2026 minimum wage, current figures reveal a widening gap between income levels and living costs.

According to an analysis published by Ekonomi Gazetesi, which relies on data from the Türkiye Cumhuriyet Merkez Bankası, a minimum wage worker would need nearly a lifetime of savings to become a homeowner—particularly in major metropolitan areas.

Housing Prices Have Outpaced Wages for Years

The data shows that the housing affordability crisis is not a short-term phenomenon but the result of a long-running imbalance. Since 2010, the minimum wage in Turkey has increased 38.3 times, while average housing prices per square meter have surged by 41 times nationwide. This divergence has made homeownership increasingly unattainable, especially in large cities.

Using optimistic assumptions—zero interest rates and allocating 50 percent of monthly income to housing payments—the required working periods paint a stark picture for a standard 90-square-meter home:

In Istanbul, a minimum wage earner would need 46.6 years (559 months) of uninterrupted work and saving.

In Izmir, the period drops to 32 years (383 months).

Across Turkey overall, the required duration is 29 years (346 months).

In Ankara, the figure stands at 26.2 years (314 months).

These timelines exceed or closely approach a whole working life, effectively placing homeownership beyond reach for large segments of the workforce.

Would a 25 Percent Wage Increase Change the Picture?

Expectations for the 2026 minimum wage have fueled speculation about potential relief. If the minimum wage were raised by 25 percent, reaching approximately 27,500 TL, the required saving periods would shorten—but only modestly.

Under this scenario, the nationwide average would decline to 23 years, while Istanbul would still demand 37.5 years of saving. Analysts warn that such improvements risk remaining theoretical, as high interest rates and persistent inflation continue to erode purchasing power in practice.

In other words, nominal wage hikes alone may not be sufficient to restore real affordability.

Car Ownership: A 16-Year Commitment

Housing is not the only area where minimum wage earners face daunting odds. Access to transportation, particularly car ownership, reflects a similar imbalance. Purchasing Turkey’s domestically produced electric vehicle, the Togg T10X, further illustrates the decline in real income.

With a base price of 2.172 million TL, a minimum-wage worker would need to save every lira of income for 196 months, or roughly 16 years, to afford the vehicle. This calculation assumes zero spending on food, rent, or other necessities—an unrealistic assumption for most households.

The figure has become a symbolic benchmark for the erosion of purchasing power among low-income groups.

Credit Limits Tighten the Financial Trap

Banking regulations add another layer of constraint. Under current rules, loan repayments cannot exceed 50 percent of monthly income. For a worker earning 22,104 TL, this caps monthly installments at 11,052 TL.

At this level, financing even entry-level housing is mathematically unfeasible given current property prices. The same limitations apply to vehicle loans, reinforcing a cycle in which minimum wage earners are effectively excluded from long-term asset ownership.

A Structural Affordability Crisis

The combined effect of rising prices, credit restrictions, and inflation has created a structural affordability crisis. Minimum-wage earners are no longer struggling only with discretionary spending but also with access to fundamental needs such as shelter and mobility.

As policymakers prepare for 2026 wage decisions, the data underscores a critical reality: without addressing housing supply, financing conditions, and real income growth simultaneously, wage increases alone may fail to bridge the gap.