The Credibility Gap: Mahfi Eğilmez on the IMF’s “Reality Check” for Turkey

mahfi egilmez

mahfi egilmez

In the latest installment of the Sesli Ekonomi series on CNBC-e, one of Turkey’s most respected economic minds, Mahfi Eğilmez, joined veteran journalist Servet Yıldırım to dissect a document that has sent ripples through Ankara’s policy circles: the IMF’s Article IV Consultation Report. For those uninitiated in the jargon of international finance, the “Article IV” is essentially a sovereign nation’s annual physical—a rigorous, data-driven assessment of an economy’s health, vulnerabilities, and future trajectory.

While the Turkish government has been broadcasting a narrative of a “successful transition” to orthodox policies, Eğilmez’s reading of the IMF’s findings suggests that the road to recovery is far steeper—and longer—than the public has been led to believe.

Prof Hakan Kara: When confidence indices rise, incumbents win

The Math of Despair: 16% vs. 23%

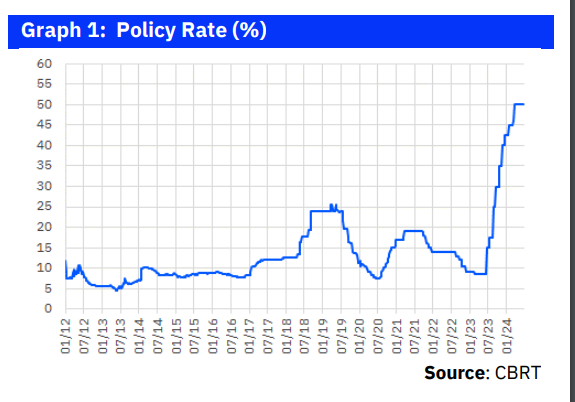

The most glaring takeaway from the discussion is the dramatic divergence in inflation forecasts. The Central Bank of the Republic of Türkiye (CBRT) and the government’s Medium-Term Program (OVP) have pinned their hopes on a year-end 2026 inflation rate of 16%. The IMF, however, offers no such optimism. According to the report, the IMF expects Turkey to end 2026 with an inflation rate of 23%.

Eğilmez emphasizes that this is not merely a technical disagreement over decimal points; it is a fundamental “credibility gap.” If an institution as influential as the IMF publicly contradicts the Central Bank’s primary target, it undermines the very “expectations management” that Finance Minister Mehmet Şimşek is trying to cultivate. According to the IMF’s long-term modeling, Turkey will struggle to bring inflation down to 15% even by 2028, effectively pushing the dream of “single-digit inflation” into the next decade.

The Great Pivot: How Mehmet Şimşek is Preparing Turkey for a High-Stakes Election Economy

The “Dream)” of Single Digits

Servet Yıldırım pointedly notes that the report uses diplomatic but firm language to suggest that without a more aggressive policy mix, the government’s goals are a “hayal”—a dream. The IMF argues that while the recent shift to tighter monetary policy is a positive step, it remains “insufficiently tight” to break the back of Turkey’s chronic inflation.

Eğilmez explains that the IMF is calling for a “determined macro-policy mix” that goes beyond just interest rates. This includes a transition to a “forward-looking” wage policy. The IMF suggests that wages should be increased based on target inflation rather than realized (past) inflation.

“It is easy for the IMF to say this from Washington,” Eğilmez remarks with a touch of characteristic candor. “But when you tell a worker whose cost of living has skyrocketed by 50% that they will only get a 16% raise because that is the ‘target,’ you lose the social contract. People only believe in targets if the government has a track record of hitting them—which, in Turkey’s case, is non-existent.”

Structural Reforms: The IMF’s Blind Spot

A significant portion of the review focuses on what the IMF doesn’t say. As an institution restricted to economic and financial data, the IMF historically avoids commenting on “non-economic” factors such as the rule of law, judicial independence, or the quality of democracy.

Eğilmez argues that this is where the IMF’s analysis fails to capture the full Turkish reality. He posits that even if the CBRT raises rates to 60% or 70%, the “expectations” of the market will not turn positive until there is a fundamental restoration of trust in institutions. “You can fix the math of the budget,” Eğilmez notes, “but you cannot fix the economy if you do not fix the law. The IMF talks about ‘vocational training’ and ‘labor market flexibility’ as structural reforms. Those are fine, but in Turkey, the real structural reform is a return to a merit-based bureaucracy and an independent judiciary.”

Vulnerability and the “External Shock” Factor

The IMF report acknowledges that Turkey’s external position has improved. The current account deficit is narrowing (forecasted at 1.4% of GDP for 2025), and reserves are approaching the IMF’s “adequacy metric.” However, the discussion highlights that Turkey remains “highly fragile” to external shocks.

Regional conflicts, energy price volatility (such as the recent spike in Brent oil), and global trade uncertainty are listed as major risks. Yıldırım and Eğilmez agree that Turkey has “no room for error.” Any premature easing of monetary policy—perhaps driven by the “election economy” pressures mentioned in other political circles—could trigger a rapid depletion of those hard-won reserves and a return to currency instability.

Conclusion: A Program at a Crossroads

The Mahfi Eğilmez review of the IMF report serves as a sobering counter-narrative to the official optimism coming out of Ankara. The IMF’s message is clear: Turkey has done enough to avoid a total collapse, but not nearly enough to win the war on inflation.

For the international investor, the report provides a baseline of skepticism. For the Turkish citizen, it suggests that the “belt-tightening” era is far from over. As Eğilmez concludes, the “normalization” of the Turkish economy is a process that requires more than just high interest rates; it requires a holistic overhaul of the state’s relationship with the law—a reform that the IMF is too polite to demand, but one that the economy desperately needs.