OPINION: Throwing cold water on Türkiye’s warming ties with China

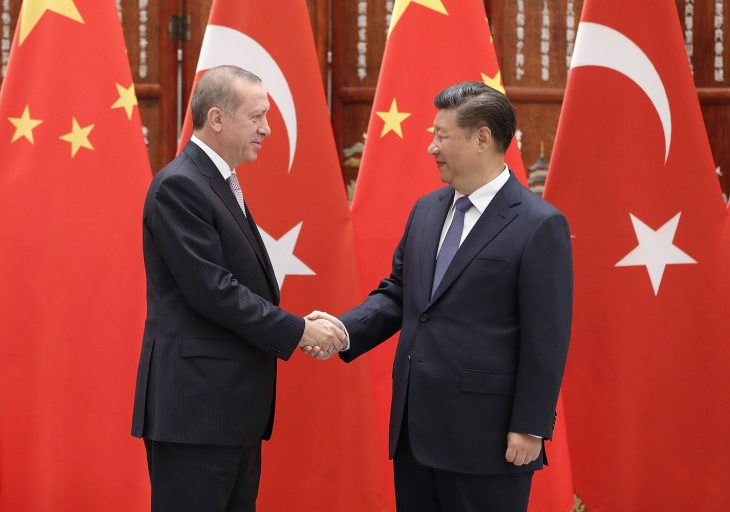

rte xi

rte xi

Summary

Rising diplomatic engagement and headline investment announcements have fueled speculation that Türkiye and China may be on the verge of a strategic upgrade in relations. Yet a closer look suggests that Ankara’s outreach to Beijing remains constrained by deep-rooted political sensitivities, modest trade ties, and lingering Chinese mistrust—leaving the European Union, not China, as Türkiye’s dominant economic partner and opening space for renewed U.S.–Turkish cooperation.

The gradual increase in high-level visits between Ankara and Beijing, coupled with a series of Chinese investment pledges in Türkiye, has revived debate over whether the two countries are moving toward a deeper strategic alignment. While relations have undoubtedly warmed compared to the Cold War era, structural limits and political trade-offs continue to cap the relationship’s upside.

A historically fraught relationship

For much of the twentieth century, ties between Türkiye and China were distant and strained, shaped by Cold War alignments and Ankara’s support for the Uyghur community. China’s Xinjiang region—home to a historically Turkic Uyghur population—briefly declared independence as East Turkestan in 1933, before being brought under Communist Party control after the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949.

As a NATO member aligned with the United States, Türkiye emerged as a destination for Uyghurs fleeing communist rule. Although Ankara established diplomatic relations with Beijing in 1971, it continued to welcome Uyghur migrants. Today, Türkiye hosts the largest Uyghur diaspora outside Central Asia, estimated at around 50,000 people, and public sympathy for Uyghur causes remains strong among Turkish nationalists.

For decades, China’s limited economic footprint allowed Ankara to pursue what many described as a “low-cost” policy of supporting Uyghurs without significant diplomatic repercussions. That dynamic began to shift as China rose into a global economic power and as Recep Tayyip Erdoğan reshaped Türkiye’s foreign policy orientation after coming to power in 2003.

Erdoğan’s three phases with China

Since the early 2000s, Türkiye–China relations have evolved in three broad phases.

Trade growth without political convergence (2003–2010).

During Erdoğan’s first decade in office, bilateral trade expanded rapidly, rising from roughly $1–2 billion to more than $15 billion by 2008, in line with Türkiye’s broader economic expansion. Erdoğan visited Beijing in early 2003, just before assuming office. However, persistent disagreements over the Uyghur issue limited political progress. After unrest in Xinjiang in 2009, Erdoğan publicly accused China of committing “genocide” against Uyghurs, sharply cooling relations.

The thaw (2010–2018).

As China’s global influence grew, Ankara recalibrated. In 2010, Türkiye’s foreign minister visited Beijing to ease tensions, pledging cooperation against “separatism and terrorism,” including anti-China activities on Turkish soil—marking the first time Ankara framed some Uyghur activism as a security concern.

High-level exchanges intensified, with Beijing hosting Erdoğan repeatedly between 2015 and 2019. Türkiye explored the purchase of China’s FD-2000 missile defense system—ultimately shelving the plan after U.S. and NATO pushback—and joined the Shanghai Cooperation Organization as a dialogue partner in 2013.

Chinese investments followed, though at modest scale. State-owned firms participated in the Ankara–Istanbul high-speed rail project, Chinese companies acquired a majority stake in Kumport port, and Alibaba bought a 75% stake in Trendyol in 2018.

Ankara also designated the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM) as a terrorist organization in 2017 and signed a mutual extradition treaty with China. While Beijing ratified the agreement in 2020, Türkiye has not.

Economic pressure and a muted Uyghur stance (2018–present).

The most significant shift came after Türkiye entered recession in 2018 and Erdoğan’s party lost major municipal elections in 2019. Facing economic strain, Ankara intensified efforts to attract Chinese capital while sidelining Uyghur advocacy.

That year, then–finance minister Berat Albayrak secured a $1 billion currency transfer from China. Parliamentary efforts to scrutinize China’s Uyghur policy were blocked, and Türkiye declined to support calls for a UN investigation into Xinjiang. Pro-Uyghur protests were curtailed, and state media coverage softened markedly.

In 2024, Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan visited Xinjiang, highlighting its historical significance to Turkish-Islamic civilization but avoiding public criticism of Beijing’s policies. Instead, both sides emphasized cooperation against what they described as terrorist threats targeting China.

Why the EU still dominates

Despite warmer rhetoric, Chinese investment in Türkiye remains limited. Chinese firms share Western concerns over Türkiye’s weakened rule of law and political unpredictability. Beijing also remains wary of Türkiye’s large and well-organized Uyghur diaspora and Ankara’s reluctance to ratify the 2017 extradition treaty.

While Türkiye’s multi-aligned foreign policy has strengthened ties with Russia and Gulf states, China stands out as a major power Ankara has struggled to draw in decisively. A Chinese consortium’s 2020 purchase of a 51% stake in Istanbul’s Yavuz Sultan Selim Bridge was smaller than expected by Chinese standards.

More recent electric vehicle investments—BYD’s planned $1 billion factory in Manisa and Chery’s $1 billion project in Samsun—appear driven less by geopolitics than by commercial logic, notably Türkiye’s customs union with the EU and Ankara’s threat to impose tariffs on Chinese-made cars.

Trade data underscores the imbalance. In 2023, China exported $45 billion in goods to Türkiye while importing just $3.3 billion. By contrast, U.S.–Türkiye trade reached nearly $40 billion and was more balanced. The EU remains Türkiye’s primary partner, absorbing $118 billion in exports and supplying $134 billion in imports.

Foreign direct investment tells a similar story. Of the $11.3 billion Türkiye attracted in 2024, EU countries accounted for 55%, while China did not rank among the top ten investors.

Implications for U.S. policy

With Chinese capital falling short of expectations, Ankara faces a strategic crossroads. At the same time, relations with Washington are improving, aided by Erdoğan’s cooperation with the Trump administration on regional issues and his personal rapport with Donald Trump.

The 2025 U.S. National Security Strategy labeled China a “predatory” trade partner, while viewing Türkiye as a middle power capable of exerting outsized regional influence. This creates opportunities for closer U.S.–Turkish coordination, including in Africa and the Global South, where Turkish firms, NGOs, and defense companies already have a strong footprint.

Washington could also engage Ankara on joint initiatives supporting Uyghur communities abroad and leverage presidential-level ties to encourage Türkiye toward a pro-U.S. neutrality on China-related flashpoints, even if Ankara avoids direct confrontation with Beijing.

Outlook

Despite tactical adjustments on the Uyghur issue and expanding trade, Türkiye–China relations remain constrained by politics, trust deficits, and economic realities. The relationship has warmed—but not enough to displace the EU or fundamentally realign Ankara away from Washington.

Author: Soner Çağaptay

(Adapted for PA Turkey by WS37)

PA Turkey intends to inform Turkey watchers with diverse views and opinions. Articles in our website may not necessarily represent the view of our editorial board or count as endorsement.

Follow our English YouTube channel (REAL TURKEY):

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCKpFJB4GFiNkhmpVZQ_d9Rg

Twitter: @AtillaEng

Facebook: Real Turkey Channel: https://www.facebook.com/realturkeychannel/***