Yusuf Ziya Cömert: Who Undermined the Belief That “The Pious Are Good”?

namaz

namaz

Summary:

Veteran columnist Yusuf Ziya Cömert questions when and why the long-held social belief that “a religious person is a good person” began to erode in Turkey. Reflecting on power, morality, and self-criticism, Cömert argues that restoring public trust in religious values cannot be achieved through rhetoric or image management, but only through genuine ethical reform and accountability.

Rising Where We Fell

Did our ancestors ever think like this?

You made a mistake. That mistake caused you to fall.

If you want to stand up again, you must abandon the mistake that caused the fall.

While reflecting on how words are understood and transformed over time, I recently came across an old article by Prof. Osman Müftüoğlu. He was speaking in the context of illness, but his insight applies to every kind of decline:

“Focus on solving the problem at the point where it emerged — in the thing that created it, the environment that produced it, and the mechanism that sustained it.”

(Hürriyet, May 20, 2016)

This is a sound and universal principle.

A Familiar Phrase, A Different Meaning

In what I often call “our neighborhood” — conservative, religious circles — this idea has long been expressed in a different way:

“A brave man rises from where he falls. Islam fell on these lands; it will rise again from these lands.”

Once framed this way, the phrase inevitably absorbs a dose of nationalism. But perhaps that is understandable. There is no need to nitpick an approach that sees itself as responsible for uplifting Muslims.

Still, the uncomfortable truth remains: wherever Muslims are to awaken from their current state — whether in our geography or elsewhere — they are today among those most visibly associated with corruption, injustice, oppression, lies, and deceit. All of which Islam explicitly condemns.

When I say “Muslims,” I am not referring to a distant or abstract world. I am speaking about ourselves. Our own society. Our own reality.

If this awakening is to happen here, where we live, that would be preferable. But only if it is real.

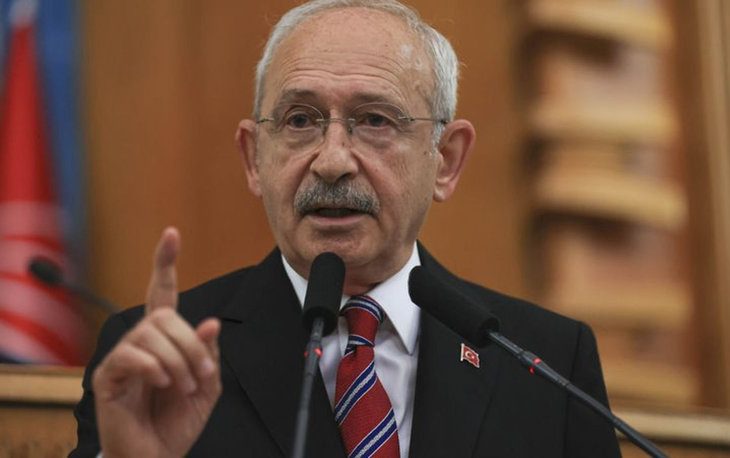

Bilal Erdoğan’s Call and a Deeper Question

Recently, Bilal Erdoğan, son of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and chair of the board of trustees of the İlim Yayma Foundation, addressed the general assembly of Türkiye’s youth NGOs.

He argued that portraying young people as a constant threat or problem is wrong and that society must move beyond pessimistic narratives imposed on it.

More strikingly, he added:

“It is imperative to once again strengthen the judgment in society that ‘a religious person is a good person.’”

This is where serious reflection is required.

When exactly was this judgment strong?

When did it begin to weaken?

Could it be that it eroded after openly religious individuals came to power?

Perception or Reality?

Bilal Erdoğan also said:

“The perception that goodness originates from Muslims must be firmly re-established in society.”

This raises a crucial distinction:

Are we troubled by a perception problem — or by a reality problem?

Do we intend to restore this belief by changing ourselves, by reforming our conduct?

By ending corruption?

By prioritizing merit and competence?

By refusing to consume the rights of orphans?

By treating people with justice and compassion?

Or do we aim instead to persuade society that what we already do is compatible with justice, merit, and fairness — and that the public simply “misunderstands” us?

In other words:

Are we saying we must become better — or you must think differently about us?

Biblical Water Crisis Is Threatening to Erase ISLAM From the Map—video

Falling, or Standing?

This is the core dilemma.

Are we prepared to admit that we have fallen — and therefore must rise again by confronting our mistakes?

Or do we insist that we never fell at all, that we are still standing, and that the problem lies solely in perception, narrative, or hostile interpretation?

These are not rhetorical questions. They go to the heart of the crisis of credibility facing religious and conservative politics in Turkey today.

Power Without Moral Renewal

The idea that piety automatically produces virtue once carried social weight. It was reinforced not by slogans, but by lived experience: modesty in power, restraint in wealth, and humility in authority.

That moral capital has been eroded. Not by secular elites, foreign plots, or social media campaigns alone — but by the visible gap between professed values and actual behavior.

When religious identity becomes intertwined with unchecked power, immunity from accountability, and selective justice, the damage is not only political. It is ethical and spiritual.

No amount of public relations can repair that.

The Need for Self-Criticism

If there is one thing we urgently need today, it is sincere self-criticism. Not symbolic gestures. Not controlled debates. Not blaming outsiders.

Real self-criticism requires asking uncomfortable questions — and being prepared to hear uncomfortable answers.

Are we ready for that?

Because without it, calls to “restore the belief that the pious are good” will sound less like moral renewal and more like a demand for unquestioned obedience.

Conclusion: Reform Before Reputation

Trust cannot be rebuilt by decree. Moral authority cannot be reclaimed through messaging campaigns.

If society no longer instinctively associates religiosity with goodness, the solution does not lie in correcting society — but in correcting ourselves.

Only by addressing corruption, injustice, favoritism, and hypocrisy at their source can any genuine moral revival take place.

Otherwise, we risk repeating the same mistake — and wondering yet again why we keep falling.

IMPORTANT DISCLAIMER: PA Turkey intends to inform Turkey watchers with diverse views and opinions. Articles on our website may not necessarily represent the view of our editorial board or count as endorsement.

Follow our English YouTube channel (REAL TURKEY):

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCKpFJB4GFiNkhmpVZQ_d9Rg

Twitter: @AtillaEng

Facebook: Real Turkey Channel – https://www.facebook.com/realturkeychannel/