David Schenker: Prospects for Syria–Israel Relations, and Turkey

israel syria

israel syria

Summary:

Prospects for more normalized—though not formally peaceful—relations between Syria and Israel have dimmed in recent months. US-mediated talks in Paris in early January offered a modest positive signal, but deep tensions persist over Israel’s security demands after October 7 and Syria’s insistence on sovereignty following the fall of the Asad regime. Israeli military actions inside Syria, Ankara’s expanding role, and shifting rhetoric in Damascus continue to complicate any path toward stabilization.

Hopes for improved Syria–Israel ties have weakened, making it notable that Syrian and Israeli officials met in Paris on January 5–6 to discuss security arrangements. The talks were mediated by US officials, reflecting Washington’s interest in preventing further escalation. President Donald Trump has said he wants Israel to “get along” with Syria, but reconciling Israel’s post–October 7 security requirements with Syria’s post-Asad sovereignty remains a formidable challenge.

Trump’s closeness to Israel has not precluded criticism. In early December, following an Israeli raid on November 28 that killed 13 Syrians, Trump warned Israel—via a Truth Social post—to avoid actions that could “interfere with Syria’s evolution into a prosperous State.” Similar frustrations surfaced earlier, after Israeli strikes in July hit Syria’s Ministry of Defense and a site near the presidential palace. Senior US officials complained that Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was acting with an “itchy trigger finger,” potentially undermining broader US objectives.

A tougher tone from Damascus

Trump is not alone in voicing frustration. Syria’s new president, Ahmed al-Shara’a, has recently hardened his rhetoric toward Israel. At the Doha Forum in early December, he accused Israel of “fighting ghosts,” claiming that despite messages of peace sent since he took office, Israel responded with “extreme violence”—including more than 1,000 airstrikes, hundreds of incursions, and the occupation of territory near the Golan frontier.

While the Doha Forum often features sharp language toward Israel, al-Shara’a’s remarks marked a departure from his earlier, more conciliatory posture. Syrian institutions have followed suit. In November, the foreign ministry condemned Netanyahu’s visit to Israeli troops in the buffer zone—previously patrolled by UN peacekeepers—as a “serious violation” of sovereignty and an attempt to impose a “fait accompli.” State media has revived the term “Zionist enemy,” a rhetorical shift that signals a troubling trajectory.

This hardening contrasts with al-Shara’a’s earlier assurances. Shortly after taking power, he said Syria had “no intention of confronting Israel” and pledged not to allow Syrian territory to be used to attack neighbors. Even on normalization, he stopped short of outright rejection, citing sensitivity around Israel’s occupation of the Golan Heights and arguing it was “too early” to discuss. Instead, Damascus has pressed for Israeli withdrawal from the UN-monitored buffer zone established under the 1974 Disengagement Agreement.

Channels of contact—and limits

Despite the rhetoric, channels have existed. Over the summer and fall, al-Shara’a dispatched Foreign Minister Asad al-Shaibani for direct security talks with Ron Dermer. More recently, Shaibani met in Paris with Israel’s ambassador to Washington, Yechiel Leiter, and the designated head of the Mossad.

Israel’s military posture in Syria

Some Israeli actions since Asad’s fall in December 2024 appear defensible. Strikes aimed at destroying Syrian weapons stocks reduced the risk of jihadist or criminal diversion. Initial cross-border deployments helped prevent a security vacuum along the Golan frontier during a chaotic transition.

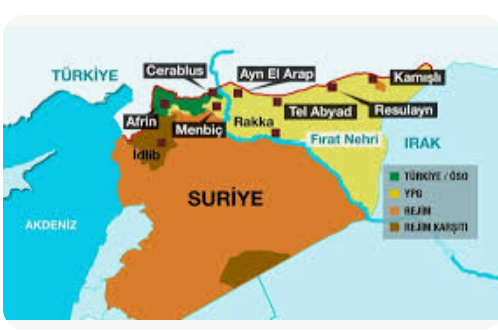

Ongoing operations also seek to counter Türkiye’s expanding influence. Israel has targeted Turkish air-defense systems and missiles deployed in—or supplied to—Damascus. In the post–October 7 environment, Israel has adopted a more forward-leaning posture, which it views as effective in Lebanon against Hizbullah.

By contrast, Israel’s intervention to protect Syria’s Druze community in summer 2025 appears less central to core Israeli security. In 2018, Israel declined to intervene when ISIS attacked Suwayda; last summer, however, Israel struck Syrian government forces after Sunni Arab militias linked to the regime attacked the same area. Israel is reportedly now arming Druze groups there.

Strategy unclear, risks mounting

Israel’s long-term strategy in Syria remains opaque. Skepticism toward al-Shara’a—given his past ties to al-Qa’ida—is understandable. Yet it is unclear what sustained kinetic pressure is meant to achieve. Israel has drawn a red line against advanced Turkish systems in Syria, but efforts to establish a new border-security regime with Damascus have not produced results.

Syria nonetheless plays a role in containing Iran’s influence. The al-Shara’a government has intercepted arms shipments intended for Hizbullah; on December 17, Syrian forces ambushed smugglers carrying dozens of rocket-propelled grenades.

Israel may believe a tense status quo is sustainable. The Trump administration appears less convinced. While hopes for Israel–Syria normalization—or Syria’s entry into the Abraham Accords—are premature, Israel’s current posture also seems to foreclose even a non-belligerency arrangement.

Arab partners in Riyadh and Abu Dhabi are invested in Syria’s stability, a reality Israel may underestimate. Robust Israeli military activity in Syria is widely viewed in Arab capitals as destabilizing, complicating Israel’s regional integration.

The US role: preventing a wider clash

For Washington, the most urgent concern is rising Israel–Türkiye friction. US mediation will be needed to establish ground rules and prevent Syria from becoming an arena for Turkish-Israeli confrontation. The United States should also intensify efforts to broker practical arrangements between Damascus and Jerusalem along the Golan frontier. The near-term objective is modest: moving Syria from a hostile neighbor toward a neutral one.

Absent Syrian acceptance of Israel’s demand for a demilitarized zone in southern Syria, compromise may be required. Without it, the prospects for stabilizing Syria–Israel relations will continue to recede.

David Schenker is Taube Senior Fellow at The Washington Institute and director of its Rubin Program on Arab Politics. This article was originally published by the Jerusalem Strategic Tribune.

PA Turkey intends to inform Turkey watchers with diverse views and opinions. Articles on our website may not necessarily represent the view of our editorial board or count as endorsement.

Follow our English YouTube channel (REAL TURKEY):

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCKpFJB4GFiNkhmpVZQ_d9Rg

Twitter: @AtillaEng

Facebook: Real Turkey Channel: https://www.facebook.com/realturkeychannel/***