Global Chess Game: A New Cold War Expands Across Continents

jeopolitik

jeopolitik

By corporate stragetist and contributor to paraanaliz.com Mr Burak Koyluoglu

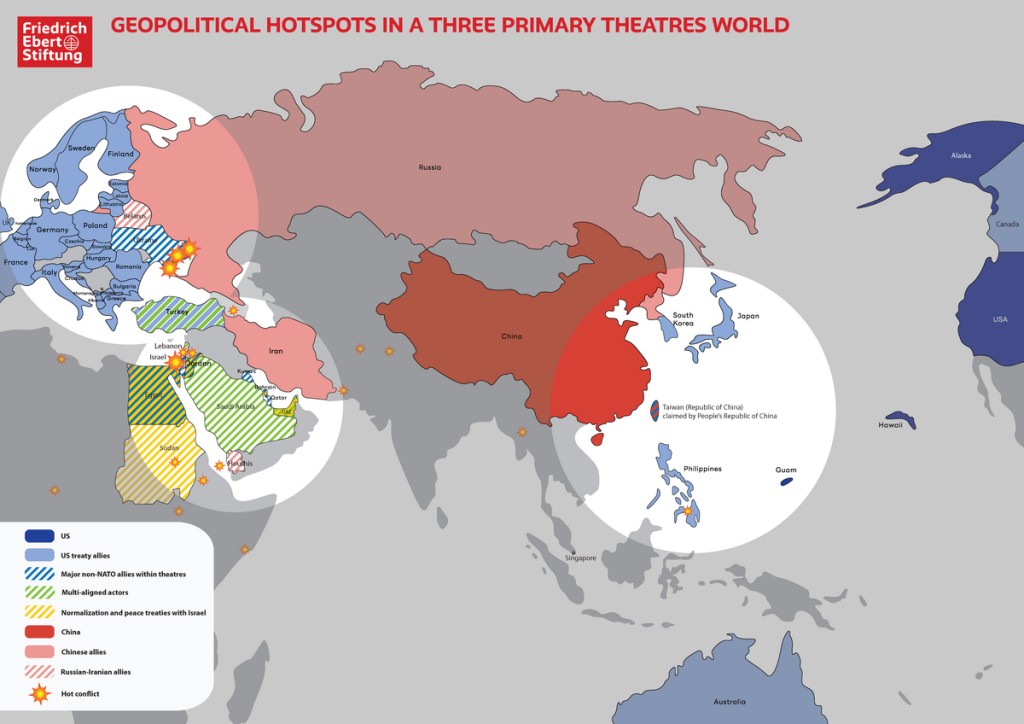

The year 2025 has been marked by turbulence on every front. The fronts of the New Cold War have not only expanded but also deepened — stretching from the battlefields of Ukraine to the tense waters of the South China Sea. The U.S.-China rivalry is no longer confined to trade disputes, semiconductor wars, or the Taiwan Strait. It now encompasses mining, technology, logistics, and even software infrastructure — the arteries of global power.

In this new geopolitical era, a fresh concept has emerged: “multi-aligned blocs.” These are hybrid, fluid alliances where countries shift positions pragmatically to maximize their national interests. India’s recent move to scale back Russian oil imports, despite its place in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, is one example.

Turkey and the Rise of Flexible Power Balancing

Turkey’s position offers a clear illustration of this hybrid diplomacy. Despite being a NATO member and a frozen candidate for European Union accession, Ankara maintains close ties with Moscow. Like India, Brazil, and South Africa, Turkey is navigating both Western and non-Western blocs, seeking to optimize its economic, political, and military advantages.

Even within the U.S.-European alliance, fault lines are visible. Despite appearing unified under the NATO umbrella, the United States and the European Union have divergent interests — particularly in trade and economic policy. Likewise, Washington’s relationships with East Asian allies such as Japan, South Korea, and Australia are more complex than they appear. These nations maintain deep economic links with China, mirroring the interdependence that once existed between the West and Russia before the war in Ukraine.

Globalization has made the 21st-century power struggle far more intricate than the bipolar rivalry of the 20th century. Capital and technology now flow effortlessly across borders, blurring the distinction between friend and foe.

From 1914 to 1990: Lessons from Earlier Conflicts

Before World War I, it was relatively simple to analyze the rivalry between the German-led Central Powers and the British-led Entente. By 1939, however, the geopolitical map was far more convoluted: Nazi Germany was allied with Fascist Italy, temporarily supported by the Soviet Union, whose raw materials enabled Germany’s invasion of Western Europe. When Hitler turned against Moscow, he sealed his own fate. By 1942, the Allied bloc — the U.S., Britain, and the USSR — had five times the industrial base of the Axis powers.

The Cold War that followed from 1948 to 1990 created a clear bipolar world: trade between blocs was minimal, and the “Third World” remained largely non-aligned. The Soviet economy began collapsing in the 1970s under the weight of inefficiency, while the West’s technological superiority determined the outcome.

By 1991, the Western world stood unrivaled — the apparent victor of history.

Clinton’s Strategic Error: Building a Rival Superpower

Yet history’s greatest strategic blunders often emerge from misplaced optimism. One of them, argues Köylüoğlu, occurred under U.S. President Bill Clinton.

Following Nixon’s 1971 visit to Beijing, the U.S. sold limited high-tech goods to China to counterbalance the Soviet Union. After the Tiananmen incident in 1989, Washington imposed military technology sanctions, but globalization and China’s abundant labor, resources, and cheap energy transformed the country into a manufacturing powerhouse.

In March 2000, President Clinton presented a bill to Congress expanding U.S.-China trade, arguing that prosperity would lead China toward democracy. His now-famous line captured the belief of the era:

“When individuals have the power not just to dream but to realize their dreams, they will demand a greater say.”

Clinton’s optimism proved misplaced. Between 2000 and 2024, the U.S. accumulated a $6.76 trillion trade deficit with China. Adjusted for inflation, the cumulative gap exceeds $7.5 trillion. This enormous wealth and technology transfer helped transform China into the world’s second-largest economy.

China reinvested its trade surpluses in U.S. Treasury bonds, effectively financing America’s public deficits and sustaining Western prosperity through cheap imports — a cycle that entrenched mutual dependence.

When Globalization Turned Against Its Architects

The irony, Köylüoğlu notes, is that while Western deficits raised domestic living standards, they simultaneously funded the rise of a rival ideological system. From Clinton through George W. Bush and Barack Obama, Washington persisted in deepening trade ties with Beijing.

President Trump sought to reverse this trajectory, but his first term was mired in political turmoil. His successor, Joe Biden, made what Köylüoğlu calls a second strategic mistake: escalating U.S. involvement in the Ukraine war. Supporting Ukraine’s NATO ambitions, he argues, was as provocative to Moscow as the Soviet missiles in Cuba in 1962.

The result was a reinforced Russia-China axis, a global energy shock, and a new wave of inflation that rattled the post-pandemic financial system. Rising interest rates and mounting fiscal stress exposed cracks in regional U.S. banks — symptoms of a deeper structural strain.

A Rebalanced World, But Time Favors the East

By 2024, the world’s three largest economies were the U.S. ($29.18 trillion GDP), the EU ($19.42 trillion), and China ($18.8 trillion) — Beijing’s output now roughly 65% of America’s.

Trump’s administration is striving to undo decades of missteps, yet time is not on Washington’s side. The Chinese Communist Party operates on long strategic horizons, while democratic systems are constrained by electoral cycles and short-term politics.

Despite its enduring technological and economic superiority, the West faces a troubling question:

Is history still working in its favor — or has the balance begun to tilt eastward?